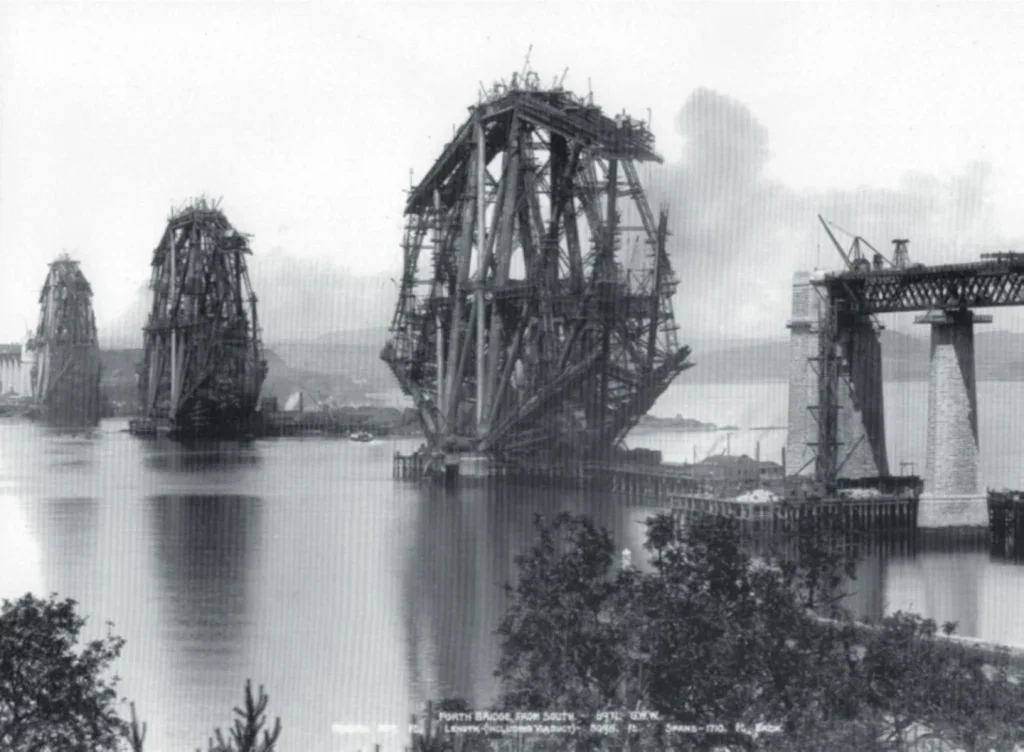

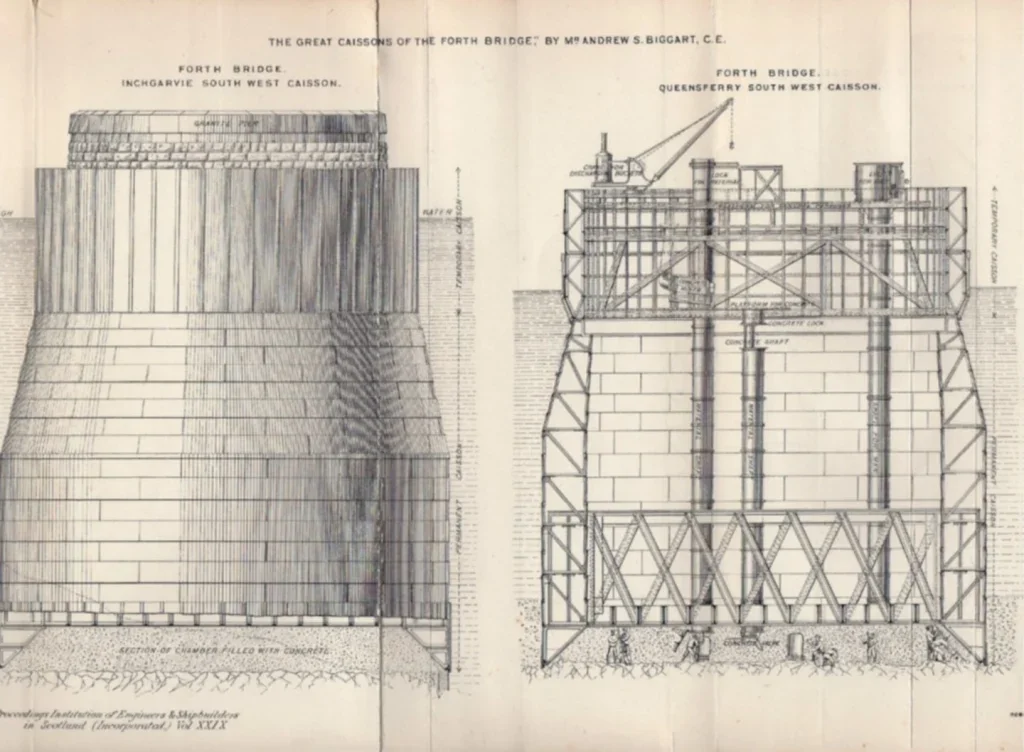

If your grandfather was involved in building the Forth Railway Bridge, and your father built bridges and tunnels, odds are that you yourself will end up as some sort of engineer.

“All I remember is that from a pretty young age, around ten, I thought I was going to be an engineer” says Alastair Biggart. “It was a fairly ill-formed thought at that time but I had no doubt about it, and when I left school I went straight to Loughborough University to do an engineering degree.

“I was born in Glasgow, because I am a Scot, but I was brought up in London because that’s where the family firm was.” The family firm was a civil engineering company by the name of Mitchell Brothers. “My father and his cousin owned it – the cousin was a Mitchell, which accounts for the name. I remember my father taking me down a tunnel he was building, I think it was a Post Office one, when I was quite young. So, yes, it’s really in the blood.”

Hardly surprising then that after university and a civil engineering degree, graduating in 1956 – and the then-obligatory two years of National Service, which he spent in the RAF and during which he learned to fly Vampire jets – he became an engineer, though not initially in the family concern.

“I spent six years as an assistant engineer, with four civil engineering contractors – Sir Robert McAlpine, Balfour Beatty, John Howard and Edmund Nuttall,” he says. “That gave me good and varied experience: there was tunnelling, there was road construction in the Scottish Highlands; I worked on the Greenock Dry Dock and on reinforced concrete and steel design. With Sir Robert McAlpine I worked on a Post Office tunnel under the Barbican in London. This was in the days when most tunnels were lined in cast iron segments. I had the good fortune to work under Jim Buchanan as Agent. He remained in charge of McAlpine’s tunnelling for the remainder of his career and made a very large contribution to the UK tunnelling scene.”

And then in 1964 Mitchell Brothers saw his services.

“I worked for them as sub-agent on the Victoria Line in London.” That was in 1965, and much of the digging was by FL22 Clay Spades. “Then I moved to Head Office with my father, who taught me the art of tendering, and soon after I was appointed a director of the firm – a clear case of nepotism! I supervised a number of small tunnel projects and then I was back on the Victoria Line again, this time on the Vauxhall Extension.”

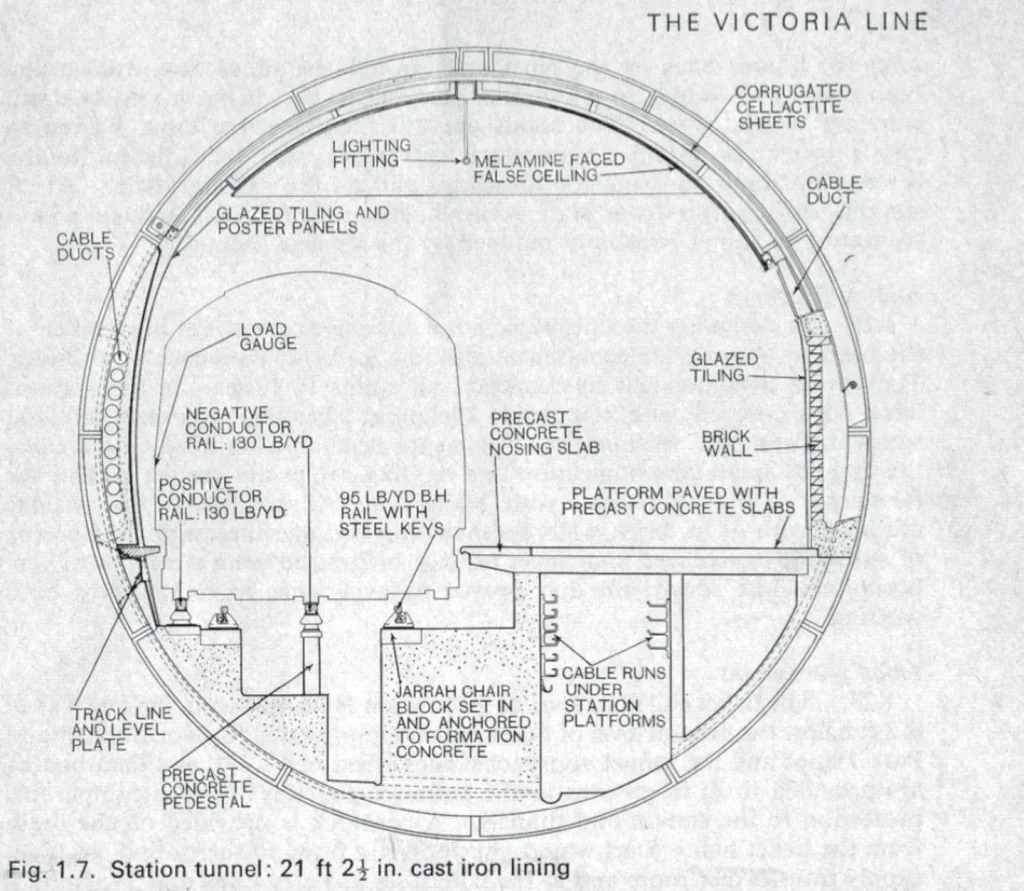

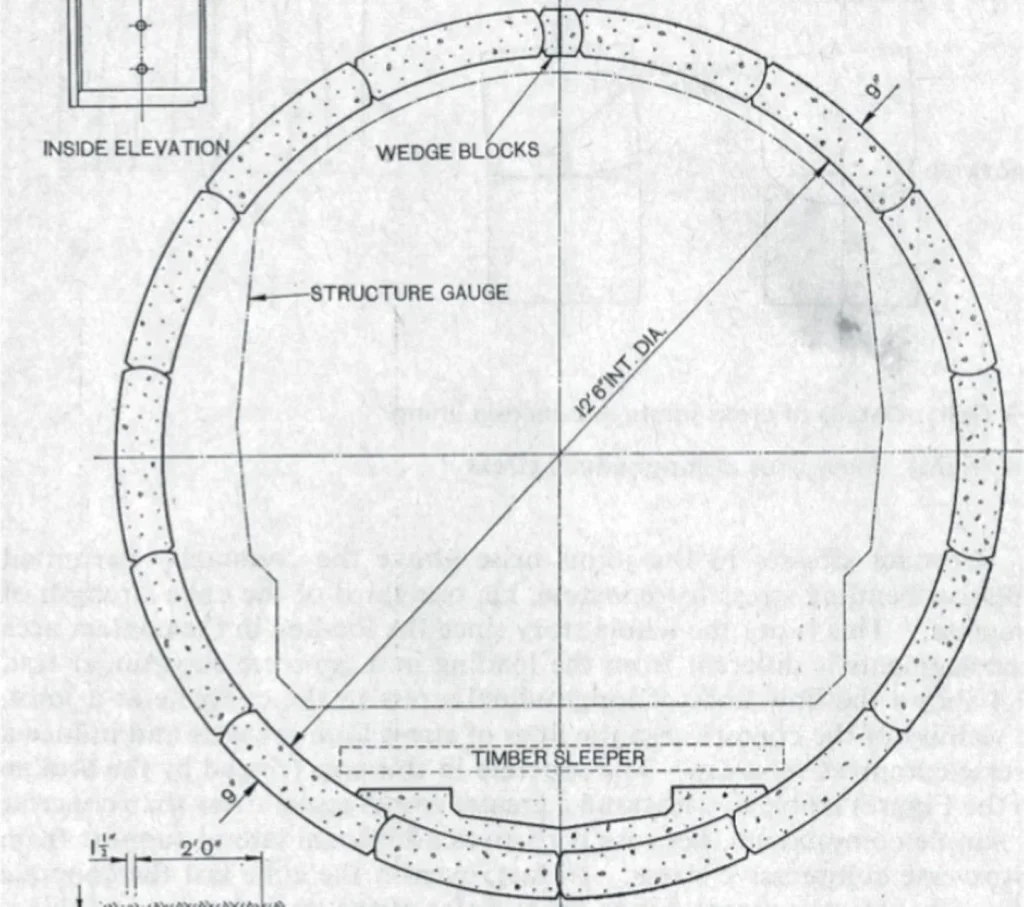

“The Victoria Line, 1965 to 1975, saw huge changes in tunnelling techniques. For one thing it rejected cast iron linings in favour of concrete. Many different designs were tried out. The consultants were Mott Hay and Anderson – they are now Mott MacDonald, of course – and Sir William Halcrow and Partners, who have been taken over long ago by an American group. Each of them designed different experimental types of concrete rings. Halcrows produced some very thin ones. Motts had a design where the segments were unbolted. At each side at axis level you put in a jack and expanded the whole ring, and then you put in concrete wedges to keep it all in place. It was very successful, though the system died out.”

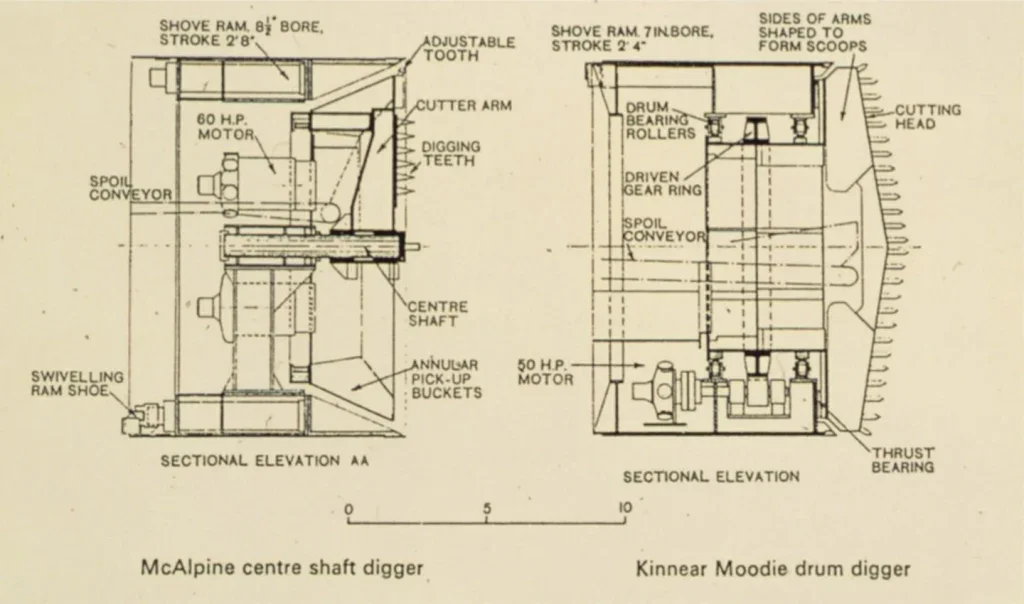

And, in place of the clay spades that had dug the bulk of the original Victoria Line the extension saw experiments with the use of cohesive ground tunnel boring machines (TBMs).

“There were two, in fact. One was the Kinnear Moodie Drum Digger, and the other the McAlpine Centre Shaft Digger. This was a UK first. The invention of the Slurry tunnelling machine and the Earth Pressure Balance (EPB) machine came later.

“In 1970, I left Mitchell Brothers and rejoined Edmund Nuttall. I was put in charge of estimating and was appointed a director of the company – no nepotism this time, so I suppose I must have earned it. And there I had a career-changing opportunity: I was put in charge of the New Cross Bentonite Tunnelling Machine experimental project. This was sponsored by the National Research and Development Corporation (NRDC). It was based on John Bartlett’s patent of 1964 for the Bentonite Tunnelling Machine, the precursor to the modern slurry machine.

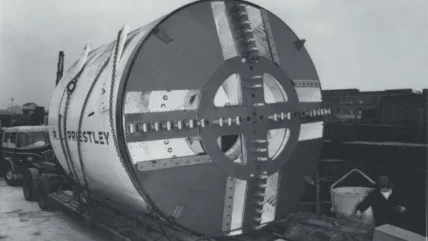

“As well as looking after estimating I was director in charge of a number of tunnelling projects and finished my time with Nuttalls as Managing Director of Robert L Priestley, a subsidiary, which designed and manufactured TBMs. One of its machines was used on the 1972 Channel Tunnel Project, which was scrapped by the government. Priestley was closed down due to lack of business, in 1982. It wasn’t until 1985 that the Treaty of Canterbury was signed with the French and the Project then really got going. The rail link was fully completed and came into public service in 1994.”

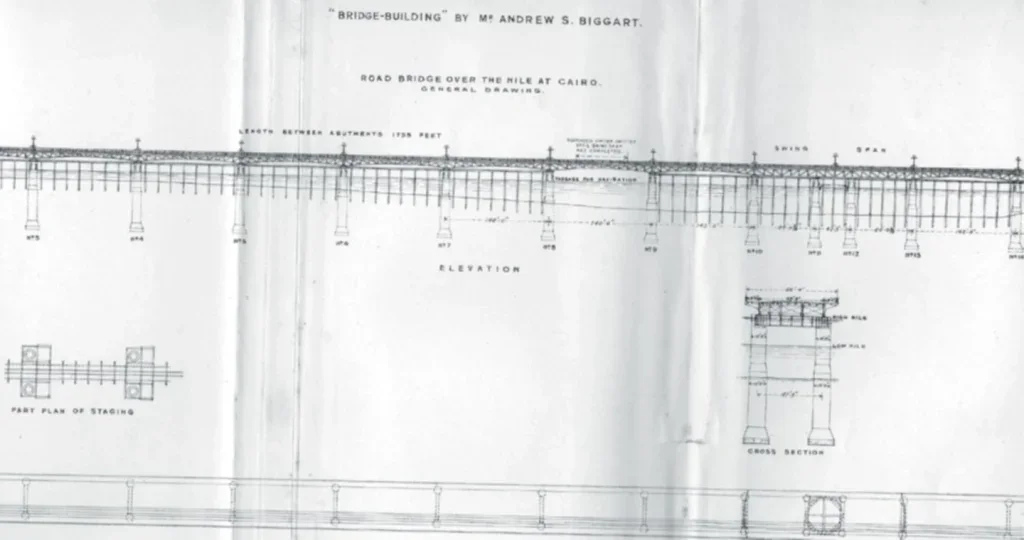

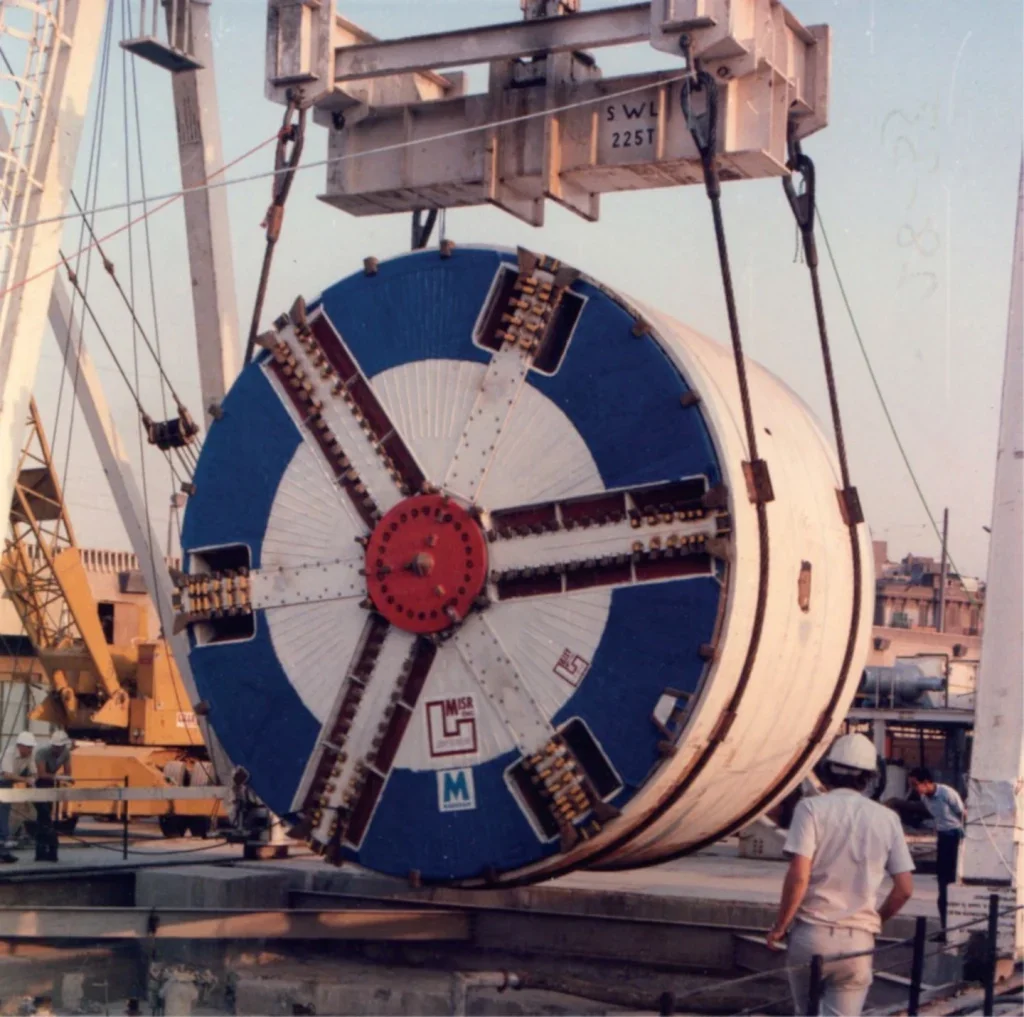

He joined Lilley Construction. “My main responsibility was tendering for overseas tunnelling projects. The next year we won a $190 million contract (£648 million in today’s money) in Cairo for new sewers. I selected the tunnelling equipment for this project – we had three slurry tunnelling machines, of 5.15m and 6.1m diameters, and compressed air equipment for shaft sinking. I was resident in Cairo for a year and a half, as Technical Director.

“Control of groundwater was essential on that project and we used ground treatment and compressed air a lot. I had worked with compressed air before, during my time at Mitchell Brothers. The Medical Research Council were updating the decompression tables and came up with what became known as the Blackpool Tables. Mitchells had an agreement with them to study the use of compressed air on an outfall tunnel in Blackpool; I had been the director in charge of the project.

“By an unfortunate irony, in Cairo I experienced the bends myself. I got it in both knees. It was very unpleasant and very painful, but you just go back to the site, into the medical decompression chamber, where they put the pressure just a wee touch above what you were working at. The pain completely disappears and they then lower that pressure down overnight while you sleep. I have had one new knee since then, but whether it was due to that or not I have no idea. Happily the new one works very well.

“It was while I was with Lilley’s in Egypt that the Channel Tunnel got under way. I thought I really ought to get on to it, so I wrote to a friend who happened to know Peter Costain (Costains, of course, were part of the TransManche Link (TML) consortium) and I asked him to send my CV to him. He did, and I was accepted. I was the assistant construction director looking after the tunnelling and the casting of the segments for the tunnel lining, which was a major operation. We cast 2.5 million tonnes of segments.”

The Channel Tunnel was the iconic project in the industry, then and now. Talk to any tunneller who was involved and they will tell you that there were things on it that went right and things that went wrong. The biggest thing at a later stage was the logistics.

“On any big project you must get the logistics right. There’s absolutely no question about it. And they did get it right on the Channel Tunnel. I don’t take responsibility for that – I joined when they had largely sorted out the method of approach.

“We had one adit that was five tracks wide, sloping, with a rack and pinion railway; that took all the materials down. We had another sloping adit which brought all the muck out on a major conveyor that had three different drive motors. All three had to go wrong before it stopped so that was fairly safe. And we had two deep shafts right down to the bottom which were about 120 metres deep, and that took the men in and out. At the peak of the project we were taking in 800 men per shift, and there were three shifts, so that was two and a half thousand men per 24 hours. And all of that worked pretty smoothly.

“And we had a great cooperation with the French. It was wonderful. They are good engineers. The one big difference was their attitude to drink and smoking. Doing either underground was a sackable offence on the UK side; they allowed both.

“I was promoted to Operations Director in 1989, looking after strategic planning for the tunnels and terminal in the UK. I was put in charge of the complex interfaces between civil construction and the installation of all the fixed equipment, and of the major construction interface between England and France.

“When all the tunnelling was finished on the Channel Tunnel, I joined Mott MacDonald and for the first time in my career became a consultant and therefore, you might also say, a gentleman. I was appointed as Tunnel Manager for the Storebælt Eastern Railway Tunnel in Denmark; after the first 6 months I became Project Director working directly for the Danish owner.

“Storebælt is a rather remarkable tunnel that outsiders will not know much about. It is not as iconic as the Channel Tunnel of course, but its construction was seen as the most geologically difficult going on in the world at the time.

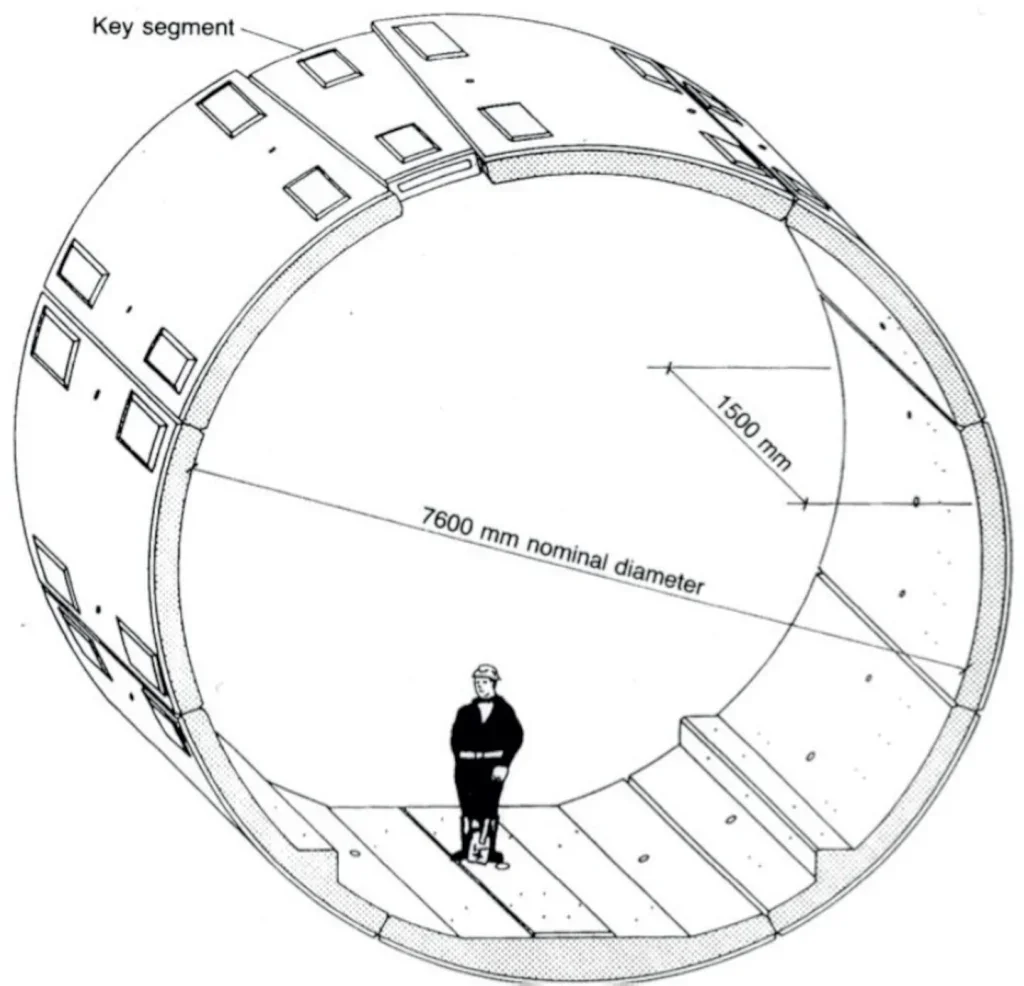

“Zealand is the main island of Denmark and has about half the total population of Denmark. The other half of the population is in Jutland on the mainland and, before the tunnel, they had ferries connecting them. The project involved 8km of twin 7.7m-diameter rail tunnels beneath the waterway, and as well as that a very large suspension bridge. The whole project was 18 kilometres long. The bridge had a main span of 1.6 kilometres and was going to be the longest in the world – but the Japanese built a bridge of their own at the same time and just got ahead of us, as their main span was 1.9 km.

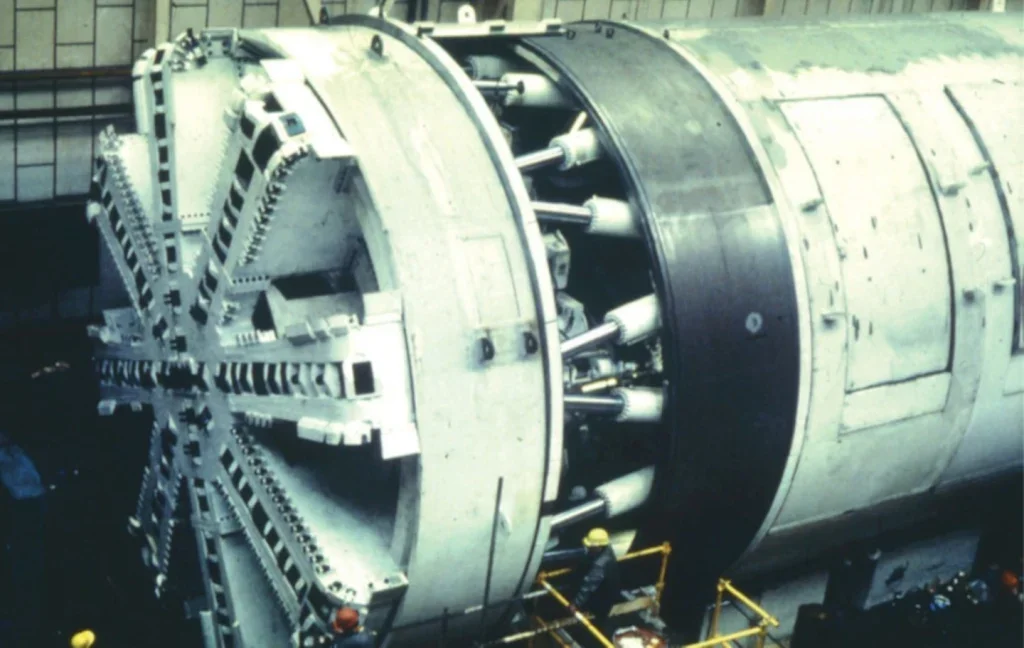

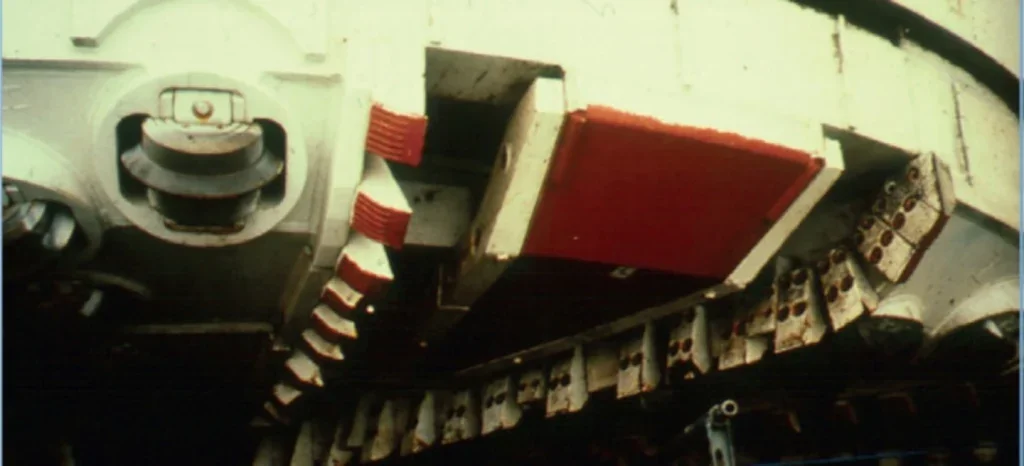

“Four large-diameter EPBMs did the excavating. Hydrostatic pressures as high as 7.5 bar had to be controlled during tunnelling.

“On Storebælt, in June 1994, we had a very serious underground fire. I am pretty sure the root cause was a burst hydraulic main and a cigarette-end: although hydraulic fluid is proof against fire because it is an emulsion, when it comes out of a broken pipe at huge pressure – they work at about four hundred bar – it atomizes and the two substances in it split and become very flammable. When it happened we got every man out quickly. No man was injured because of the fire but it completely destroyed the TBM. We had 16-inch thick concrete segments and they were burnt down to six inches. The fire raged for about 19 hours, as I remember. If it had gone on any longer the segments might have burned through and we would have had an inundation.

“The problem then was how to fix the damaged segments. Fortunately, I remembered that on the Channel Tunnel we had some very thin cast iron linings left over. They were only about 60mm thick. They weren’t quite the right diameter, but by machining the joints and putting one extra segment in we produced a cast-iron lining that would fit inside the concrete one: we just erected it inside then grouted it in place. And because it was so thin it didn’t affect the clearance for trains. Segment linings can now be made fire resistant by the very simple use of polypropylene (PP) fibres mixed in with the concrete. This prevents the spalling that nearly destroyed our tunnel.

“A really fascinating thing at Storebælt was that we dewatered the ground ahead of us. We called it Project Moses. We were excavating through glacial tills and the hydrostatic pressures were as high as 5 bar. To reduce it we put wells down through the seabed. The power to these wells was supplied by floating barges; there were six or seven of them across the 8 kilometres, so about one every kilometre, and the wells went down through the glacial till that we were tunnelling through into the marl below and extracted the water out of the marl. That, therefore, reduced the hydrostatic pressure in the marl and that in turn had the knock-on effect of reducing the pressure in the glacial tills.

“Some clever guy in the contractor’s side had been doing some dewatering somewhere and had seen a reaction about a kilometre away and put two and two together and applied it subsea at Storebælt, and that enabled us to reduce the pressure at the face by two atmospheres. So if we were in a depth of water that would have needed five atmospheres of face pressure we could reduce that to three – which was a huge benefit because that is an acceptable pressure for men to work in. So that allowed the personnel to enter the cutterhead under compressed air and maintain the TBM cutters.

“Cross passages were a particular problem on Storebælt and virtually every known ground treatment was used to consolidate the ground. This included vacuum wells, freezing with brine, chemical grouts and silicates and microfine cements.

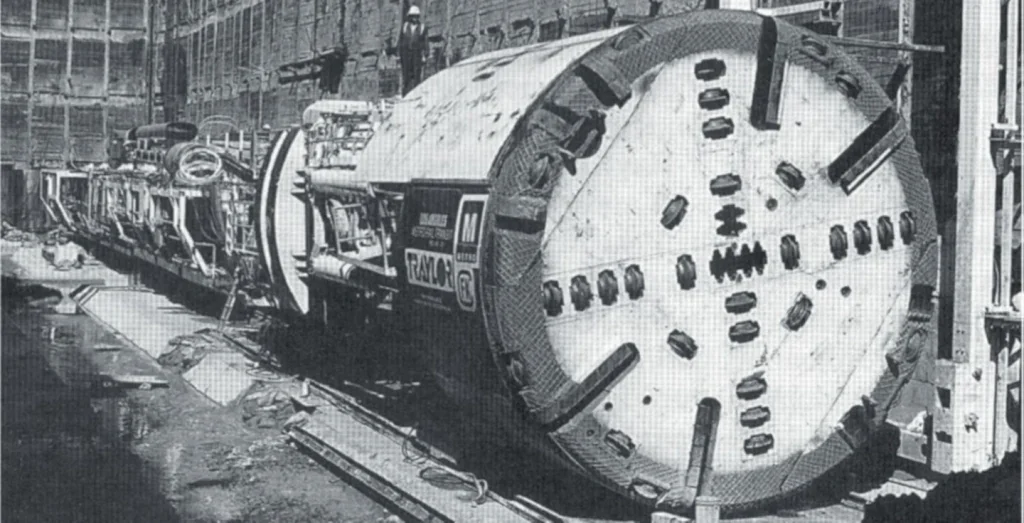

“In 1995, at the end of my time on Storebælt, I returned to Mott MacDonald and went out to California as Project Manager in charge of Construction Management on the $1.5 billion Metro Red Line North Hollywood Project in Los Angeles. This project included 10 km of twin railway tunnels, three underground stations and all the railway systems. Control of groundwater was a particular problem. TBMs and blasting were both used for underground excavation. Part of the tunnel was under Hollywood Boulevard. Our first task was to raise the Gold Stars on the sidewalk. I stayed on this project for four years, after which I joined Mott MacDonald’s office in California for a further two years.”

In 2002, Biggart set up on his own as a consultant. “I swapped a hard hat for a desk. The challenges are totally different. I could do a lot of it from my desk, but of course you have to visit the projects. And it is different being a consultant because you are watching and trying to remember the whole time, especially if you’ve been a contractor. If you try and give advice too much they charge you for your interference. If you start to advise them how to do it, they will say; ‘Well you told us to do that!’ But I enjoyed the change.

“I found that even though I was consulting I was learning a lot at the same time. Which is a thing that always happens: if you act as a consultant to people, you learn from their mistakes. And if you are lucky they don’t blame you for those mistakes.

“Being a consultant you have to know the technology as well as management techniques. You cannot manage something if you don’t know the technology. When you start to give advice you have to know a lot about all the details of the subject. Happily, over my career although I have been on the whole managing the projects, I have always taken a great interest in the technology.

“So, for instance, one of the projects I worked on as a consultant was the Saint Clair River Tunnel in Canada/USA. I and one or two other people were called in as a small team. One of them, Les Hampson, is a superb tribologist who knows everything there is to know about the theory of moving surfaces and is therefore very expert on seals and in particular TBM main bearing seals.

“The TBM was 9 meters diameter, which was the biggest closed face TBM that had been used in the USA and Canada at that time, and the company had been used to making much smaller machines. They had used for the cutterhead bearing seals just the same very small seals that they had for all their other small machines and had not taken into account the fact that when you put on the pressure at the face of an earth pressure balance machine it will flex the bulkhead and flex the cutterhead a bit where it engages with the face. And, mistakenly, they had put the seals on the radial face rather than axial face. If they are on the axial face, if the front bit moves against the rear piece the seals can just move slightly on the surface that they are engaging on. But if you put them on the radial face the seals would get crushed. That’s exactly what was happening. It was only discovered when bits of seal were squeezing out through inspection holes.

“Between us we gave them advice to change the whole sealing system, which they did just before they started driving under the river. It worked well, so that was good.”

Biggart had been involved with seals since his earliest days at Priestleys. “As I said, we were designing and making tunnel boring machines there. Main bearings in those days weren’t so big – around four or five metres – and the seals that we used went right round them and were made in a giant mould, in one piece. It was very difficult to get the diameter absolutely spot on.” Today there is a solution that is for sale in every high street: “Now you can make those seals just in long strips, and you can calculate the length that you need. You make a scarf joint at each end, and you join the two ends with superglue. Superglue is amazing stuff. It takes the stress and strain of going round and round about ten thousand times. So this was a big advance in the design of seals.

“Of course that is just one of the advances that I have seen during my career. I think one of the most significant was the gradual or rapid change from cast iron to concrete linings. It was all cast iron when I started in 1958. The Post Office tunnel that I first started my career on, for example, was cast iron and the joints were caulked, believe it or not, with asbestos rope impregnated with cement. At least one colleague of mine died of asbestosis, and I am sure that a lot of those caulkers must have died from it as well.

“The art of designing segments now is well developed. In the early days each segment had a sort of well in it to make a space for the bolts to go in. That has completely changed. Now you have an arrangement where the bolts go in at an angle just from a small tapered hole, and the sealing system is now fantastic. You expect to have a dry tunnel, which in itself is a huge advance.

“For the future, I think we are getting towards the limits of size for TBMs. There is no doubt that machines may be slightly bigger in diameter than the EPBM for Alaskan Way in Seattle at 17.43m or the slurry machine used at Tuen Mun to Chek Lap Kok in Hong Kong at 17.6m, but, in the end, I think it will be the huge differential pressure over the face as the TBMs get bigger and bigger that will be the limiting factor. I had the privilege to advise on both these projects.

“It is stating the obvious to say that AI will play a large role in the future. It can cover matters such as ring erection at the face, automatic addition of additives at the face of closed face TBMs, grouting and the like. The depth that TBMs can operate at will be no longer limited by the workers’ ability to work in high pressures. Instead of people down there, AI can be used to produce robotic working.

“Construction materials will continue to improve. This is especially true of things such as environmentally-friendly concrete and the use of carbon fibres. The industry as a whole, of course, is working hard to produce an environmentally-friendly concrete that takes less heat to produce. Concrete underground can also act as an emissions-free heat source. In building with deep piles in cities, they often put the pipes for ground-source heat pumps into piles: they put the pipes in along with the reinforcement. That’s environmentally friendly. You can do the same thing with tunnels. You have the pipes buried in the segments, and you join those all together, so you have a source for the ground source heat pumps. I don’t know of any tunnel that has used such a system yet. It’s probably still at experimental stage but it would seem a very promising concept.

“I think of the changes I have seen in sixty years of tunnelling and am sometimes astonished. Instead of the huge and dirty muck waggons that we used to see there have been gradual improvements in the long conveyors, which are becoming more and more common in TBM tunnels. Welding has largely replaced rivets. There is virtually no hand digging at the face.

“A very high percentage of tunnelling in waterbearing ground is now done with closed face TBMs, slurry machines and EPBMs, both in their infancy when I started work. The New Austrian Tunnelling Method (NATM), now called Sprayed Concrete Lining (SCL), had not been invented back then. The introduction of lasers to control TBM positioning was a game-changer – that was around 1962. More important than any of those is the Health and Safety at Work Act, which came in in 1958, the year that I started work. That must have saved many lives.

“For the future, control systems will continue to be ever more sophisticated. As with motor cars there will be an increasing use of a central electronic brain in TBMs. EPBMs and slurry machines will continue to improve. In the case of slurry machines this may be through a further development of the slurries and cleaning plants; in the case of EPBMs the use of foam will no doubt be further refined.

“But the need for tunnels is going to remain. When I compare in my mind the state of the art as it is today and what it was when I started work in 1958 I am truly amazed – so anything is possible for the next 65 years. Tunnels on the Moon are quite likely and maybe Mars!”

CHANNEL TUNNEL PAY – A MOVE FROM CASH

If you want an example of just how old-fashioned things were just those few years ago, the building of the Channel Tunnel brought about a major change in the law that affected all employment since.

“The law as it existed back then said that every person had the right to receive their pay in hard cash,” says Biggart. “At peak eight thousand people were working on the Channel Tunnel, just on the British side. Trying to pay that number in cash each week would have been a nightmare for cashiers; so the powers that be went to the Government and said, ‘We’ve got to do this job properly. You will have to change the law.’ And they did. I think that was the beginning of the end for cash on site.

“It meant of course that if they wanted to work on the job the employee had to have a bank account, and that was new for some of them too. So it was also a gift for the banks.”