Only two months ago, though a long time after it had to start to fight for its chances against the alternative of a bridge for a coast-to-coast link over the Fehmarn channel between Denmark and Germany, the tunnel option won political backing as the favourite. No small feat considering it would mean building the world’s longest immersed tube tunnel – a 17.6km long structure, slightly shorter than in earlier design studies.

On 1 February, Danish politicians gave the state-owned developer of the EUR 5.1bn (USD 7.24bn) project, Femern, the sign-off needed to support its preferred option and move forward with design work for the road and rail link, and have construction underway by 2014 and the tunnel open by 2020, later than previously expected due to longer time needed for environmental investigations and the approval process.

But first, and though Denmark is funding the development of the project to cross the 19km-wide, relatively shallow but busy shipping channel, the approval of German authorities will be needed, environmental approvals gained and an act of parliament obtained to give legal permission for the new bi-national connection to be established.

Geotechnical investigations in the channel continue and studies are expected to finish next year, which is also when the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is to be submitted and an application made to the German authorities. The construction bill for the Fehmarn tunnel is to be submitted to the Danish parliament (Folketinget) in 2013 – which is around the time the verdict from the German authorities is expected.

The countries signed a treaty in 2008 to build the link, which their respective Governments ratified it in 2009.

Rival designs

Choosing between the bridge and tunnel options for the Fehmarn crossing has been no simple task to carry a four-lane motorway (dual 2-lane) and two-track electrified railway. Early on the initial studies and outline analyses tipped in favour of the cable stayed bridge but the relative advantage seen at that point was not secure enough to eliminate the immersed tube alternative. The tunnel survived into a further round of studies and design refinement, this time by consortia of consultants working on parallel, independent tracks. Competing, in effect.

Either means of building the link would, however, see the chosen structure step onto the podium of world-class rankings. To pass over the shipping lanes, the cable-stayed bridge would have required the largest spans built, and the immersed tube would be among the world’s longest – even with a ventilation island about midpoint, though the need for that aspect of the tunnel could possibly be designed out.

Then, late last year, after the additional studies, designs and site investigations, the client announced its preferred option was the tunnel.

Financially, it was seen as a close run race. Unlike before, it was the tunnel that had the edge in construction budget terms. However, the tunnel was assessed to be more expensive to maintain and operate. The payback periods for the toll-fee projects are about the same – 30 years. The client says that, from an overall financial perspective, there is no difference between the bridge and tunnel.

However, the tunnel is expected to present fewer risks in both the construction and operational phases. While the tunnel would be an extremely long structure, it wouldn’t call for the boundaries of technology to be pushed to the same degree as required to build the cable-stayed bridge. The tunnel was judged as likely to cause less long-term impact than the bridge, and also it would be safer for ship traffic in the channel.

After recently receiving backing of Danish politicians for the tunnel option, Femern chief executive, Leo Larsen, says: “We welcome the political support for our recommendation that the future link be designed as an immersed tunnel. The decision means that Femern has reached an important milestone in the planning of the fixed link.

“As our conceptual design projects are based on an extremely thorough, technical foundation we can now focus on ensuring that the authorities approve the project.

Danish hub

Denmark is becoming an increasingly important transport and economic hub in northern Europe thanks to the series of major infrastructure projects built in the last two decades and the Fehmarn crossing to come.

First, the Storebelt (Great Belt) project joined the peninsular and island parts of the country with a combined road and rail link, then the Oresund Crossing established a fixed link for road and rail over the relatively short expanse of water between Copenhagen and Malmo, Sweden, and with the Fehmarn link the road and rail network will be plugged more into the main part of Continental Europe.

Already the Copenhagen-Malmo axis is blooming economically, and metro links in each city have been improved. In the Danish capital yet more investment is taking place with tunnelling set to start in 2012 for the 15.5km long Cityringen addition to the network. Last year, Malmo opened a new rail link.

Next, the Fehmarn link, says the client, will cut travelling times between mainland Europe and Scandinavia, allowing high-speed train services to operate between main cities and creating a new, and important, growth area in northern Europe. The key axis is foreseen to be Hamburg with Copenhagen/Malmo.

The date for the link to open has shifted over time. Early studies thought 2015 might be possible, and then in the initial stages of the tunnel squaring off against the bridge the timetable was for construction to start in 2013 and the link to open in 2018. Following the lengthy competitive analyses, the latest revised schedule sees construction start a year later than planned and the link to open to two years later.

Fehmarn tunnel concepts

As the variety of bridge design variations were assessed to give the competitive best chance against a tunnel, and included suspension as well as cable stayed structures, so too was there a refinement process undertaken for the tube options.

The client has had a separate team working with a different consultant JV on the bridge option. Early cost estimates, given in 2008, the year before the twin track design studies got underway put the budget for the bridge option at EUR 4.5bn (USD 6.4bn), or about 18 per cent less than that for tunnel cost of EUR 5.5bn (USD 7.8bn).

The work was done by a client team working with a JV of consultant – Ramboll Danmark with Arup and Tunnel Engineering Consultant (TEC), which were supported by subconsultants – WTM Engineers, HTG Ingenieurburo fur Bauwesen, Wilkinson Eyre Architects, Schonherr Landskab and Oriental Consultants.

The immersed tube design has been favoured over a bored tunnel solution since the early days of examining the possibilities for a fixed link across the Fehmarn channel. Even as far back as the feasibility study completed in the late 1990s the immersed tube was viewed as the more robust alternative.

However, the possibility of bored tube was not ruled out in the most recent studies despite the focus being on an immersed tube, for which the majority of design variations were examined – more than 10, or almost double that for a bored tunnel. They were compared on a range of parameters, such as robustness, environment, safety layouts, ventilation, time to build, risks, cost, constructability and connecting into the road and rail networks ashore.

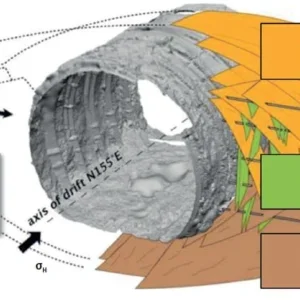

For the immersed tube, during the design assessment stage the indicative size of the immersed tube tunnel was gauged as needing to be about 40m wide by 9m high to hold a two cells for rail lines and two for road traffic, all side-by-side.

There was also examination of how, and whether, to eliminate the ventilation island in the middle of the channel. The ventilation design and use of space inside the tunnels were, therefore, crucial aspects to help reach a conclusion on what might be possible, and to recommend.

Immersed tube – selected

Femern recommended an immersed tube tunnel design that is 17.6km long – approximately 900m shorter than envisaged in earlier studies thanks in part to a revised alignment and also the design of shore areas to match those for the rival bridge design.

The tunnel will be about 43m below the channel at its deepest point. Fehmarn tunnel will be the deepest immersed tube carrying both road and rail traffic. The tunnel will be formed of dozens of precast concrete elements that will be floated out and placed into excavated trenches in the seabed along a mostly straight alignment.

Excavation of about 15.5Mm3 of seabed – about a quarter less than previously thought – will be dredged to form the trench to hold the immersed tube tunnel. Once backfilled and covered, the tunnel will also be covered with a 1.2m thick stone layer for protection against shipping and anchors.

When looking at constructability, a key consideration was to find yards not too far away that could cast elements that are at least 200m long and weigh about 70,000 tonne.

In the elected design, the immersed tube elements are notably longer than in the 1999 feasibility study – 217m versus 150m-175m, or at least almost a quarter longer – though they are of the same order of size in height and width, albeit a little shorter and thinner, at 8.9m and 42.2m, respectively. At about 73,500 tonne, the elements are about 8 per cent heavier.

An element has four cells and these run its length; when the tunnel is complete the cells form continuous passages for road and rail traffic from coast to coast. In the fehmarn design the two road cells are each 11m wide and the pair of rail cells are 6m wide – a little wider and narrower, respectively, than previously considered in the earlier concepts. The cells are all 5.2m high within elements that have an overall 8.9m element height.

The figures are for standard elements because the Fehmarn also calls for special elements to be inserted at 1.8km intervals. There will be 10 special elements in addition to the 79 standard elements.

The special tunnels were conceived to take advantage of the length of the tunnel to concentrate the M&E equipment requiring space and maintenance at these dedicated areas, located at regular intervals. The special elements are wider than standard elements, adding a further 2.7m to the overall width, and they are deeper too – by 4.2m to accommodate a number of additional cells below the road and rail cell decks from access to the technical rooms. The special cells also provide space for recesses beyond the emergency lane in the road cells where service and rescue vehicles can park without disrupting traffic.

Eventually, the construction work will be undertaken through a design and build contract. Preliminary calculations suggest it will take 6.5 years to build the tunnel.

Tunnel portal at German coast Tunnel portal at Danish coast Location of the Fehmarn Tunnel project to link Denmark and Germany An immersed tube tunnel for road and rail travel below Fehmarn channel Seabed geology has been investigated to help rival bridge and tunnel designs