WATERCARE’S CENTRAL INTERCEPTOR – PROJECT BACKGROUND

In 2019, Ghella Abergeldie Joint Venture (GAJV), was awarded the contract to build the Central Interceptor, the largest wastewater project in New Zealand’s history. The client is Watercare.

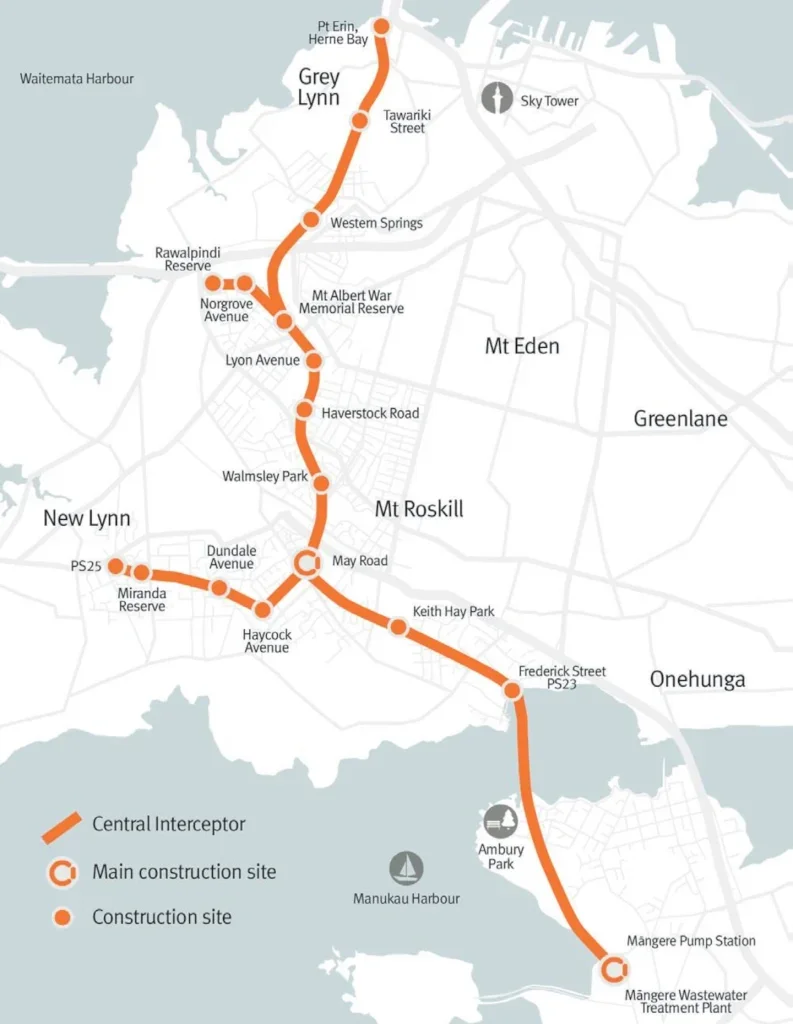

The Central Interceptor (CI) will run between the Māngere Wastewater Treatment Plant in the south of Auckland and Point Erin in the north. The 16.2km-long, 4.5m-diameter tunnel will run between 15m to 110m deep under the city. Along the route it will connect to the existing wastewater network, which will divert flows and overflows into the tunnel.

With another micro tunnel boring machine (MTBM), CI has also completed boring two smaller ‘link sewer’ tunnels, totalling 4.3km in length.

The Central Interceptor will reduce wet weather overflows into waterways and beaches by up to 80% in some places, helping to make them significantly cleaner.

Approaching the end of 2024 – with tunnelling approximately 83% complete and the project 71% complete overall – it is an opportune time to reflect on Central Interceptor project’s approach to health and safety.

CHALLENGES IN NEW ZEALAND’S CONSTRUCTION SECTOR

New Zealand’s workplace safety record, while better than that of the United States, Canada, and France, remains concerning. According to the Business Leaders’ Health and Safety Forum report, ‘State of a Thriving Nation’, workplace fatality rates are almost twice that of those in Australia. The Report likens New Zealand’s situation to that of the UK in the 1980s. More mature regulatory frameworks and firmer enforcement, the absence of ‘no fault’ worker schemes, more active trade unions and better client engagement are cited as the key factors positively influencing workplace safety performance in Australia and the UK.

Historically, New Zealand has had a ‘brain drain’ of experienced migrants to Australia where there is better pay and more opportunities, especially in the construction sector. A new ‘fast-track’ pathway to Australian citizenship for New Zealanders, announced in April 2023, will likely tempt more to make the move across ‘the ditch’. It is also worth noting that Central Interceptor client Watercare (WSL) did not have the ‘inhouse’ expertise to deliver such a large project.

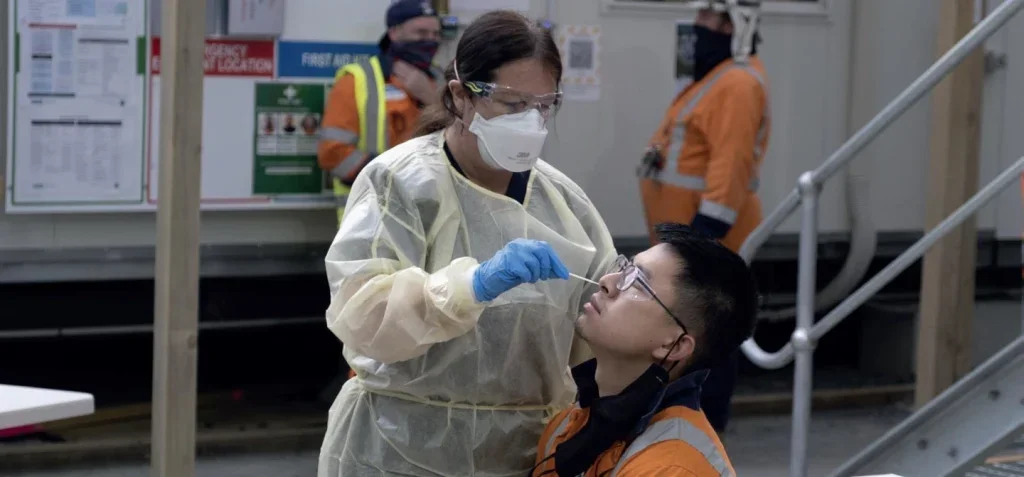

To compound the problem, in 2019, when construction on the Central Interceptor started, Auckland’s City Rail Link (CRL) project was also underway, creating more stress in an already oversubscribed labour market. The Central Interceptor project also had to navigate the complexities of operating under Covid-19 restrictions and also the impact of a rare 1 in 200-year storm event.

To help tackle some of these challenges, WSL created a ‘blended team’ comprising its existing WSL staff and experienced professionals from consultancies Jacobs and Aecom, respectively, many of whom have significant international tunnelling experience.

CLIENT APPROACH

WSL is an organisation that takes safety seriously. However, in the case of the Central Interceptor project the leadership team recognised many of the above issues early on, and decided that things would have to be different. The organisation had experienced a tragic accident in 2011 that resulted in a fatality and multiple serious injuries after gas seeped into a section of underground pipe and exploded. CI’s Programme Director was intimately involved in that accident and was determined that health and safety would be pivotal to the delivery of the Central Interceptor project.

Shayne Cunis, WSL Chief Programme Delivery Officer, says: “From the start we had the view that success on the project was not about building world class infrastructure as we knew we had the team to do that, but rather everyone going home safe free from harm. It has been a relentless journey to date, but everyone involved in the project has been committed to achieving this vision.”

One of the earliest decisions, seemingly unrelated to safety, had a significant cultural impact. The expectation was that the Central Interceptor project team would be based at Watercare HQ in Newmarket, but the WSL project leadership decided against that. Instead, the entire client team would be based out of rented office space at Eden Park Stadium some three kilometres from central Auckland. This choice helped foster a unique culture: the team’s location, paired with the excitement of working in New Zealand’s largest stadium, helped distinguish the project from the corporate environment, encouraging, among other things, a fresh perspective on safety.

GOOD TO GREAT

Central to this novel approach to safety on the Central Interceptor project was the ‘Good to Great’ (G2G) initiative. During the tender process the leadership team made a conscious decision to go, as the American author Jim Collins would put it in his management book, from ‘good’ to ‘great’. In 2020 the joint project team (WSL & GAJV) signed up to a broad set of commitments that would lay the foundations for what was to come. The initiative would be funded by WSL and was viewed as an investment in health, safety and wellness. Embedded into this was a set of jointly agreed, project-specific Values that helped to further create the Central Interceptor project’s own distinct identity and also meshed well with family-owned Ghella and Abergeldie.

It is also where the commitment to ‘collaboration’ was first formally documented. The WSL Central Interceptor project leadership would hold firm on this despite others over the years intermittently insisting that a ‘policing’ approach is a better way to manage contractors, rather than collaborating with them. Collaborating with our GAJV colleagues on safety would become the Central Interceptor project’s modus operandi.

The G2G commitments encompassed various aspects of project execution, e.g., site supervision, training, competence, etc. The project’s two-day long induction is a key component. Everyone working on the project is required to attend. It is delivered at a purpose-built training centre located near to the main worksite at Māngere.

In addition, anyone working underground is required to attend an additional two days of training. The training is high quality and well thought-out, with a variety of speakers that keep attendees engaged.

More importantly the WSL and GAJV Project Directors attend the first day to introduce themselves, the project and to make clear its ambition to be the safest job site any of them have worked on. At the conclusion of the second day, these leaders personally distribute Central Interceptor project identification cards during a ‘graduation’ ceremony, reinforcing the project’s commitment to safety.

GAJV Project Director, Francesco Saibene, says: “The ‘Good to Great’ initiative has been an essential approach to elevating Health, Safety, and Wellness standards. The focus on continuous improvement and collaboration between WSL and the GAJV has been instrumental in fostering a culture of safety and wellbeing.

“This dedication to excellence, supported by leadership visibility and regular site inspections, has created an environment where health, safety, and wellness are ingrained in every aspect of work, pushing the project from ‘good’ to ‘great’.”

ENHANCING MORALE AND WELFARE

Project inductions are nothing new, doing them well is obviously key and the Central Interceptor project scores well. However, as stated G2G contained a wide range of commitments, which were expanded as the project progressed. Below are examples of some of its key elements. It’s the changes that these commitments made to the conditions of those working on site that have made the most impact, in terms of improving morale.

Good morale is an essential building block of a positive health and safety culture; it’s almost impossible to have good safety performance without it. That’s assuming the term ‘safety culture’ is still relevant (Sherratt, Szabo, & Hallowell (2025), Seeking a scientific and pragmatic approach to safety culture in the North American construction industry).

MEALS

To start with, subsidised hot meals are provided to all workers, something unheard of in New Zealand on such projects. This was a major commitment by WSL, logistically and financially; at its peak the GAJV were providing on average three hundred meals a day to workers across sixteen work sites on both day and night shifts. With the work being physically demanding, the importance of having a regular hot nutritious lunch every day (or night) should not be underestimated. Having lunch delivered to sites daily also had an added benefit during Covid restrictions in that workers didn’t have to leave site, reducing the risk of exposure. Fresh fruit is also delivered to every site three times a week. For individuals, it was something less to have to think about every morning, and the more focused and nourished people are at work, the better and safer it is for everyone.

PPE

The provision of high quality, branded PPE also made a huge difference to workers.

At the two-day induction all attendees are provided with a full set of PPE: shirts; trousers; boots; hat; gloves; safety glasses; fleece; and, raincoat. Task-specific PPE is also provided where required. This is not unusual for projects in other countries, but it is highly unusual for New Zealand.

Not only that, but PPE is given to subcontractors who are encouraged to take it with them when they leave the project. The strategy for subbies was to give them high-quality PPE so they could go back to their parent organisations wearing it. Invariably the smaller contractors wouldn’t provide such gear and turning up for work on a cold Monday morning wearing hi-vis trousers and a nice warm hi-vis fleece would obviously be a talking point. Providing good PPE to everyone working on the project is one thing, trying to bring about change, even surreptitiously on a small scale, in the supply chain is another.

SITE SET-UP

Well laid out site welfare facilities are also a differentiator. Clean and well-appointed drying rooms, hygienic lunchrooms/areas, pre-start briefing areas – which in many locations are heated – and designated traffic and pedestrian routes are the norm. A laundry service, delivered as a Māori-owned business, is also provided for dirty PPE.

These are things that many readers will expect as standard on a major project, however they are anything but in New Zealand. For workers this is something different for them, it helps them realise that the Central Interceptor project is serious when it comes to their safety and welfare.

A special note on coffee machines: the WSL CI Project Director, on visiting the GAJV head office (after having just come from a nightime site visit), observed a state-of-the-art coffee machine in the kitchen. What ensued next has become an urban legend, suffice to say that all of the project’s site welfare cabins are now furnished with identical coffee makers. Another, albeit small, example of where the Central Interceptor project leadership were focussing attention, and there would be many more examples to come.

The G2G initiative provided the blueprints for what would be become not only a strong safety culture but also a profoundly ‘collaborative’ working relationship between client and contractor. Details on how it was financed and managed commercially is another discussion. Suffice to say that it helped bring to life many of those items taken for granted on major projects in other parts of the world; on the Central Interceptor project it has had a profoundly positive impact on those working at the coal face.

SAFETY VISION & LEADERSHIP COMMITMENTS

In 2022 the Central Interceptor project’s leadership decided that further work was needed to clarify their position on safety. Up until then the project had been asking its workforce to comply with various safety requirements, many of which are discussed at the project induction. Although the commitment to safety by the WSL leadership was implied, there was nothing that anyone could point to specifically. A half-day workshop was held where a new ‘Safety Vision’ and a set of ‘Leadership Commitments’ were developed.

All members of the Leadership Team attended, again with the WSL & GAJV Project Directors setting the bar and direction. Safety Vision cards were printed and sent out to all staff; these would also become a key component of the two-day induction to the Central Interceptor project. The Safety Vision strap line, “I Think Safe – We Work Safe – We All Go Home Safe”, is now a staple in communications, quoted at pre-starts, progress and board meetings. A set of eleven Health, Safety & Wellness leadership commitments were agreed upon and signed. Large posters of these commitments, complete with signatures, were printed and adorn meeting rooms and site pre-start areas for workers to see.

The Leadership Team regularly attend site to personally push the message home. The annual safety climate survey incorporates these commitments, asking the workforce for feedback on how the leadership is performing against them. Again, this is another example of where the WSL & GAJV Leadership Team had their focus.

BEACON SITE

Inspired by a similar scheme in London, the Beacon Site concept is simple: set criteria for site standards that far exceed minimum legal requirements and recognise the sites that achieve. For Beacon on the Central Interceptor project, it’s not the high standards that make it work, it’s the way in which the scheme was developed and how it’s managed that is important.

This was a client-led initiative with the GAJV agreeing to pilot the scheme at the Western Springs site. The first thing was to sit down and agree the criteria; in other words, collaborate. WSL didn’t want to push this onto the GAJV, that simply wouldn’t work, discretionary effort was the goal.

Site assessments are conducted jointly by senior WSL & GAJV Leadership adding credibility to the process. If a site meets the criteria an award is made, and although the whole site is recognised for their efforts, it’s the Site Supervisor who gets the ‘unofficial’ accolade. Beacon Site awards get widely publicised across the Central Interceptor project and it’s the intent of the scheme to create something to strive for, and to motivate Site Supervisors in the process (it helps that they are a competitive bunch).

A special set of Beacon criteria was also developed for the TBM and tunnel environment.

What is extraordinary about the Beacon Site initiative on the Central Interceptor project is the extent to which it has been ‘absorbed’ into the GAJV’s culture. It is now completely administered by our contractor colleagues and has become part of their management system. This was always the client’s intention – to hand Beacon over to the contractor but the enthusiasm with which it has been met was unexpected. Collaborating on its development and demonstrating proof of concept undoubtedly helped, in doing so each party could clearly see the value in such an initiative.

RECOGNITION SCHEME

Employee recognition schemes are a dime a dozen, every reputable organisation has one sort or another. CI is no different, but it’s the way that its run that gives us what we refer to as ‘the one degree’. The phrase comes from a conference the author attended in the USA in the early 2000’s. The pitch then was “it’s just one degree that’s makes the difference”. Converting from Fahrenheit to Celsius, water does nothing at ninety-nine degrees, but at one hundred degrees it does something miraculous, it starts to boil, going from liquid to steam.

Recognising people, or teams, for being safe, or finishing a piece/section of work safely is what we aim for.

On CI the approach comprises three levels, as awards: entry level; Champions; and, Excellence.

The entry level award, inspired by a similar scheme on the 2012 London Olympics, is a ‘There n Then’ which can be given by anyone and comprises, as the name suggests, an on-the-spot award of a NZ$30 voucher. The criterion is simple, if you think someone is doing a good job, and doing it safely…give them a ‘There n Then’. A photo must be taken of the person receiving the award, so it can be distributed throughout the project (peer recognition).

The next level is HS&W Champions Award. These are agreed by the senior WSL & GAJV leadership and comprise a framed certificate signed by both the WSL and GAJV Project Directors and also NZ$200 worth of vouchers. Importantly, these are presented at pre-starts when the entire site team is gathered (again, peer recognition is key).

The highest level of award is the HS&W Excellence Award. At the time of writing only five have been handed out. A professionally framed certificate along with NZ$2000 to the recipients’ nominated charity is given. However, in this instance the certificate is usually handed out by the CEO of Watercare and/or the equivalent within the Ghella, Abergeldie and Jacobs organisations. These awards are not only widely publicised across the project but also end up on LinkedIn and similar sites.

There is nothing radical about the Central Interceptor project’s recognition process. The fact that there is only one process that is applied equally within the GAJV and WSL is certainly of importance. The quality of the certificates, the framing, the signatures, the way these awards are presented and communicated are all meticulously curated. We go the extra ‘one degree’.

MOCK TRIAL

At the beginning of the Central Interceptor project the newly formed Leadership Team looked overseas for examples of good HS&W practices. Tideway in London was one obvious choice due to the similarities between it and the Central Interceptor. The team was impressed with their immersive ‘EPIC’ programme. In an effort to provide their own ‘immersive’ experience, and to drive home the safety message with WSL site engineers (known as Site Representatives or just ‘Site Reps’), the WSL H&S Team worked with their local law firm partners to develop a realistic scenario that would bring the WSL Site Reps and senior Leadership to experience a court setting – in a real court.

The scenario was methodically pieced together, with lawyers visiting the actual site of the mock incident. Each role was painstakingly written, briefed and rehearsed. The drama played out in a courtroom at Auckland University Law School and defendants were greeted on arrival (without prior warning) by cameras and a TV news crew. Their reactions were genuine. The court session was run following proper protocol with the whole event being filmed. This was as real as we could make it, even Peter Jackson would have been impressed! Seats in the public gallery were limited but a debriefing session was held with the entire WSL team after. The event or ‘immersive experience’ was such a success that the GAJV are now in the process of developing their own scenario, and WSL is collaborating on its development.

CONCLUSION

Safety management on the Central Interceptor project has effectively integrated lessons and initiatives from other similar projects, tailoring them to meet local needs. Client and contractor engagement in safety has been exemplary, with pro-active involvement since the project’s inception. The ‘Good-to-Great’ initiative will serve as a template for major projects to follow.

The project eschewed the traditional client/contractor relationship and the client effectively partnered with their GAJV colleagues on safety, delivering low accident and injury rates.

Plans are now underway to ensure that an ‘archive’ of material is easily accessible by other clients and contractors across New Zealand. The project intends to leave a legacy for others to build on.