Iceland has an approach to tunnelling that seeks the rock to play the prime role in road tunnel performance without, as often elsewhere, significant and heavy use of permanent concrete linings, where possible. The approach builds on the drill and blast excavation heritage of the Norwegian tunnelling sector.

However, as a large island nation in the north Atlantic, sat square upon a spreading ridge of parting tectonic plates, the geology of Iceland continually presents complex and varying combinations of rock and groundwater conditions to fascinate, frustrate and typically surprise, despite best efforts. The geological challenges that arise on road tunnel projects are complex and, for tunnellers, do crop up as different challenges with some frequency.

Most commonly, the tunnelling challenges feature two excavation problems: faults zones of varying size; and, lots and lots of water – usually cold, but not always. Most recently, the geological challenges have shown particular extremes on the Vadlaheidi toll road tunnel project, located in the mid-north of the country, closest to the Arctic Circle. The progress of excavations at Vadlaheidi have been drastically slowed, with both drives from the portals hindered by different problems.

On the east side, tunnelling was brought to a halt in early 2015 by a forceful combination of the two core problems – weak shear zones and massive inflows, respectively. After some months, and following a massive pumping effort, work is ongoing to stabilise and recover the tunnel.

On the west side the problem is water again, but of a different character. The challenge is twofold: large inflow rates, and the groundwater has been extremely hot, temperatures lessening only of late. A massive grouting regime is in place, merely to obtain the chance to edge the face onward.

Tunnelling on the project has been very challenging, remarks Bjorn A. Hardarson of consultant Geotek, which is providing site supervision services to Vadlaheidi project.

Being Iceland, the geological challenges at Vadlaheidi are not the first time significant excavation challenges have been experienced in road tunnel construction, merely the latest and affording fresh opportunities for tunnellers to face and solve seemingly continuous problems, and struggle on.

The roster of road tunnels is being added to despite the technical challenges; success comes eventually, and is needed. The benefit to be won is having all-weather subterranean routes, liberating more of the remote, scattered, towns and communities along the freezing fjordic coastlines, and those tucked in snowfilled valleys, over long dark winter months.

Among road tunnel projects built in recent years are the Hedinsfjord, Almannaskard, Faskrudsfjord and Oshlid schemes. Under construction are two key public road projects – Vadlaheidi and Nordfjordur, which are the country’s longest two road tunnels; and, at Husavik – an industrial haulage tunnel route only, on which tunnelling was nearing completion as Tunnels & Tunnelling went to press. Projects to come in the near term include Arnarfjordur- Dyrafjordur for which prequalification is underway, says Gisli Eiriksson, director with Vegagerdin (Icelandic Roads and Coastal Administration).

As plans are etched and firmed in the far north, potential projects for the future could include road tunnels at Sundabraut in Reykjavik, Mid-Austurland, a further subsea tunnel below Hvalfjordur, and schemes potentially also at Lonsheidi and Vopnafjordur-Herad.

Vadlaheidi

Vadlaheidi is Iceland’s second longest road tunnel, though it has the largest cross-section profile of a tunnel open to public traffic. It is a single tube being built to run east-to-west from Fnjoskadalur, an inland valley, to Eyjafjordur, the long fjord opening to the north while back south, at the head of which, is the region’s principal city, Akureyri.

The tunnel is approximately 7.5km long, including 320m of concrete portals, which keep access clear of the deep and widespread snow each long near-Arctic winter. Within the mountain, geology is basalt with interbedded sedimentary layers. Excavation had anticipated mixed face conditions.

The excavation challenges have proved more extreme, the project has been delayed and construction is still underway. Vadlaheidi has had possibly the most challenging tunnelling experience of road tunnels in Iceland so far. Once completed, though, Vadlaheidi will provide an all-weather route to open up communications and economic opportunity year-round, expanding the regional network of such roads around Akureyri.

The strategic effort to improve all-weather transport in the region had its most recent major investment at the Hedinsfjord scheme, opened in 2010. It is located north of Akureyri, and is farther from the town than Vadlaheidi. Until Vadlaheidi is finished, Hedinsfjord can boast having the longest road tunnel (Olafsfjordur – 6.93km, plus portals) in the mid-north of the country.

The Hedinsfjord project was developed by the roads authority, Vegagerdin. During construction, Hedinsfjord had its own significant geological challenges in tunnelling due to groundwater, though not as much as Vadlaheidi has been experiencing.

Project developer for the Vadlaheidi road tunnel is Vadlaheidargong Ltd, which took on project development from the road authority, still acting in a design role on the project. The project works are funded by a state loan, to be repaid through toll revenues. The toll road tunnel was planned to be in service by late 2016. In the project procurement stage, bids came in too high or so close to the available budget that the Ministry of Finance was called upon to re-assess the cost-benefit of the project.

Following the review, the main characteristics of the project design were re-affirmed: a single tube tunnel with a finished width of 9.5m at carriageway level and clearance height of 4.6m above the surface. Running through a mountain range that edges a fjord, Vadlaheidi’s is not only to be Iceland’s second longest road tunnel in the near-term it also has the largest profile (T9.5, 66m2). The cross-section is enlarged at regular intervals to provide turning bays and service recesses.

The unit price construction contract was awarded to Osafl, a joint venture of Swiss firm Marti and Icelandic company IAV.

The JV submitted the lowest of the four bids and was the only tenderer to come in below the project budget, albeit tight to the limit. Site supervision services are provided by Geotek and Efla.

Tunnelling work involves a total of 7.2km of drill and blast. Excavation started in Q3-2013 at the west side of the project, a little way from Akureyri and easily accessed. It wasn’t long before the initial complexion of excavation problems were met, however, and they only kept building.

A year into the tunnelling, by late 2014 the face had advanced only slightly more than 3.2km. The original construction schedule anticipated tunnelling to be completed by late 2015, but the scale of the geological challenges thwarted that goal, and tunnelling still continues on the project. Most recent data, from the end of August, show the excavation has advanced a total of almost 5.9km – or slightly more than 81 per cent – of the length of the single tube to be blasted through the rock. But, as Geotek’s Hardarson notes, there remains only 1.35km of excavation to be completed.

The distance advanced may have been only slowly added to but the achievement in the circumstances have been gargantuan, especially given the radically different, and extreme, geological conditions the tunnellers have encountered: hot on one side and cold on the other.

Both wet. The different challenges have been constant for the tunnellers to contend with patiently as the west and east faces slowly close upon each other, now barely a few kilometres apart through the rock.

Vadlaheidi: West side story

Tunnelling on the Vadlaheidi project started on the west side but after advancing 1.9km the progress rate dropped on meeting sustained geothermal inflows. Extensive grouting was tried with limited success.

With the temperatures of the rock up to 60oC, the geothermal inflows got up to about 46oC. Steam formed near the face, and much of the tunnel approach had reduced visibility, affecting working hours as well as sequences of activities such as mucking out.

The hot water and humid conditions became so difficult that work was stopped, temporarily, in August 2014. From coming into contact with the geothermal zone, the face had only slowly advanced another 825m in the worsening conditions.

The aim on the project, then, was to switch effort to the other side of the tunnel – on the opposite side of the mountain range. However, just over half a year into those works, the east side ran into its own problems in early 2015. So severe were the problems that the focus of construction activity had to switch back to the mothballed west side.

After an interval of about nine months, therefore, tunnelling resumed on the west side, in May 2015. Having had time to prepare, though, the works on the west side were able to resume supported by extra ventilation equipment to handle the hot and humid conditions, and introduction of an even larger-scale regime of grouting, with a two-part mixture.

But as the excavation slowly advanced uphill (at 1.5 per cent grade), the temperature of the hot inflows continued to increase, eventually peaking at 65oC. Probing is being done 30m-40m ahead of the face. Large volumes of grout were injected into the rock mass ahead of the face to stem the scalding flows, reducing the inflows sufficiently for each blast round to advance the face.

It was not clear if it would continue higher still, nor where and how the geology would eventually change, in the rock ahead, into the cold water zone experienced by the flooded, static tunnel on the east side.

By the end of 2015 the contractor had completed approximately 3,135m of excavation on the west side, or approaching two-thirds of the planned drive for that section. Temperatures, however, were beginning to pull back, slowly.

So far this year, tunnelling on the west side had advanced approximately a further 1,250m as Tunnels & Tunnelling went to press. Inflow temperatures are down to half their peak level. Progress has been around 20m-40m per week, typically, adds Hardarson. Occasionally though there is a surge, like more than 60m achieved in a week in late August.

In total, by late August, the west side has advanced more than 4,380m – almost 88 per cent of what has been planned for the section. Excavation on the other face, though, has yet to properly resume following the extensive recovery works.

Vadlaheidi: East side story

Tunnelling on the east side of the project started earlier than planned due to the slow progress caused by geothermal inflows on the west side. Excavation got underway in September 2014 and quick progress was achieved – in under two months the face had advanced about 380m.

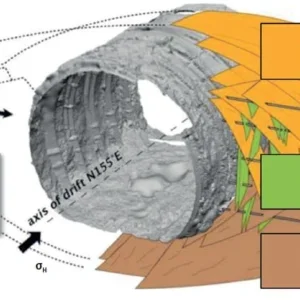

Excavation pushed on, advancing downhill, until early 2015 when a sub-vertical fault zone that had been passed without problem then gave way without warning in a progressive collapse. No one was injured.

The face had already moved beyond the fault into reasonably okay basalt and was set to advance farther when the roof began to collapse some metres back. Cold water inflow began and continued, steadily, and deepening to eventually flooding most of the length of the tunnel. From the face, the tunnel was fully submerged for about 600m back uphill, then partly flooded up towards, but short of, the portal area.

The works on the east side have been focused on recovery of the tunnel. As such, given the extensive pumping and then continued dewatering required, and stabilising the tunnel in the weak zone, the east side has made little progress for almost one and a half years.

The tunnelling work involves extensive consolidation grouting for stabilisation, and the grouting above the tunnel started in February of this year. To slowly open up the fault zone, heavy excavation support comprising pipe umbrella, steel beams, lattice girders, wire mesh and more than plenty of shotcrete.

By the end of August, the east side was still using the grout and stabilisation system to work through the weak zone, to at least recapture the previously held advance of 1,475m before the collapse and flood. The zone is about 15m thick, and water still emerges from the tunnel face, remarks Hardarson.

Nordfjordur Project

The Nordfjordur project is located on the east coast of Iceland, near the town of Eskifjordur, and key infrastructure is a 7.9kmlong single tube (including about 370m of concrete portal structures). The total length of the project ranks Nordfjordur as the longest road tunnel under construction, and will be the longest in service when opened, expected in late 2017. It also includes approximately 7km of access roads.

Vegagerdin is developing the road tunnel. The scheme was approved by the Government in early 2012, saw construction start in late 2013 and achieved completion of the excavation phase two years later, in late 2015. Contractor on the project is a JV of Metrostav (completing its second road tunnel in Iceland – the first was leading the JV that built Hedinsfjord) and local firm Sudurverk. With completion and fit-out works well underway, Eiriksson says the road tunnel is to be officially opened to traffic in September 2017. Plans and designs for the project were developed by local consultants including Mannvit, Verkis and Efla.

Tuff challenge

Geology along the tunnel alignment is mostly layers of basalt with variable scoria near the boundaries. There are also sedimentary layers, notably orange-red tuffs, presenting layers of variable thickness. Unusual for an Icelandic road tunnel, little groundwater was expected – and there was relatively little experienced.

The tunnelling challenge was in the weak tuffs, primarily at the south side of the tunnel, near Eskifjordur. Excavation rates would often drop by three-quarters when the face would advance from drill and blast method in basalt rock and approach the dry sedimentary layers. Extensive support was required to carefully advance through the tuff layers. The steps included pre-dig installation of a canopy of poles, and then installation lattice girders and shotcrete at each 2m, short-step, advance of the face on those stretches.

The halfway mark in excavation of the T8 profile tunnel (8m wide at the base) was reached in during 2014. With progress having continued as anticipated, tunnel breakthrough on the project occurred just over a year ago, in September 2015.

The contractor is now half-way through two further years of construction activities to complete and open the road tunnel to traffic, in 2017 – an opening schedule that has remained steadily on course. Current work includes installation of the waterproof lining and technical stations within the tunnel, and also on construction of a total of 366m of concrete portal structures.

Husavik, future Projects

The Husavik tunnel project is located in the mid-north of Iceland, farther northeast than Vadlaheidi from the regional main city, Akureyri. Husavik is one of the shortest road tunnels built in recent years, at slightly more than 1km long, including the relatively short portal structures. Its excavated width and maximum height are 11.3m and 7.6m, respectively – making it the largest cross section of any road tunnel in Iceland. However, the tunnel is only for use by industrial trucks to reach Husavik harbour, and is not for open public traffic use.

As Tunnels & Tunnelling went to press, breakthrough at the tunnel was expected around September, says Eiriksson. On the project, Geotek has been providing site investigation services.

Eiriksson adds that the Husavik project is expected to be fully completed and officially opened to traffic in approximately a year – about September 2017. The timing of the opening almost coincides with the scheduled opening of the country’s longest road tunnel, Nordfjordur.

The Arnarfjordur-Dyrafjordur project is located in northwest Iceland, cutting through the mountain chain separating the fjords of Arnarfjordur and Dyrafjordur. Geology in the area is again basalt with interbedded sedimentary layers. The total length of the road is approximately 5.6km, including concrete portals. Prequalification for the construction work on Arnarfjordur- Dyrafjordur is underway, and excavation is expected to start by mid-2017, says Eiriksson. The scheduled opening of the tunnel is Q3-2020.

The second subsea tunnel below Hvalfjordur, near Reykjavik, has been looked at as a toll crossing. In the same area of the country, the Sundabraut scheme has been examined as a double tube tunnel.

Should it be built, it is the Mid- Austurland scheme that could grab the record for length in future, and by a long margin. Nearby, to the north and south, respectively, could also be the Vopnafjordur-Herad and Lonsheidi projects.

Steadily, and despite what its never-dull geology throws up, Iceland is adding to the number of road tunnels being built around the coastline to provide better access and all-weather links to its scattered communities.