The underground is a frontier with immense potential for addressing urban challenges, yet its development is fraught with complexities that demand technical finesse and strategic collaboration. For architects, planners, engineers, and designers, understanding the intricacies of subterranean spaces is not just an advantage—it’s essential for creating and managing resilient and functional cities.

In cities like New York, Singapore, and Helsinki, underground developments have transformed urban landscapes. The New York subway system and the Oculus transportation hub exemplify the integration of functionality and design, creating spaces that serve millions while offering architectural inspiration.

Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands development showcases how underground spaces can combine infrastructure with high-end retail and leisure, optimising land use in one of the world’s densest cities.

Meanwhile, Helsinki’s Underground Master Plan demonstrates foresight by strategically allocating subterranean zones for utilities, parking, and recreational facilities, preserving surface areas for green spaces and pedestrian use.

However, the success of these projects hinges on resolving a triad of challenges: stakeholder management; multi-use design; and, competition for limited underground space.

THE CASE FOR UNDERGROUND DEVELOPMENT

Urbanisation, climate adaptation, and land scarcity are driving cities below ground. Here’s why:

- Optimising space use: Relocating transit, utilities, and storage underground frees up surface land for green infrastructure, affordable housing, and public spaces. For instance, Helsinki’s ‘Underground Master Plan’ includes subterranean car parks, data centres, and even sports facilities, unlocking space above ground and making the surface more liveable and sustainable.

- Enhancing resilience: Underground spaces shield critical infrastructure from extreme weather and rising sea levels. They can also serve as emergency shelters during natural disasters. Japan’s ‘G-Cans Project’, a series of massive underground flood water reservoirs, for example, protects Tokyo from typhooninduced flooding.

- Improving connectivity and liveability: By integrating transit hubs, pedestrian pathways, and utility systems, underground spaces reduce surface congestion and enhance accessibility. The RÉSO network in Montreal offers 33km of underground walkways, connecting metro stations, shopping centres, and offices while shielding pedestrians from harsh winters.

These examples demonstrate the transformative power of underground development—but achieving this vision requires addressing a host of technical and stakeholderrelated challenges.

STAKEHOLDER DYNAMICS IN SUBTERRANEAN DEVELOPMENT

Underground projects are inherently collaborative, requiring coordination among a wide range of stakeholders. Urban planners and architects focus on harmonising subterranean and surface-level systems, ensuring aesthetic and spatial integration. Engineers and developers address the technical complexities of structural integrity and geotechnical constraints while striving for cost efficiency. Policymakers and regulators are responsible for balancing economic growth with zoning laws, safety standards, and long-term urban resilience. Crucially, local communities play a central role, as their support—or resistance—can determine the fate of a project.

Take London’s Crossrail project, for instance. Its success lay in early and sustained engagement with councils, residents, and heritage groups, which allowed the project to mitigate disruptions and address community concerns.

Similarly, Tokyo’s flood mitigation infrastructure, known as the ‘G-Cans Project’, involved extensive consultation with local stakeholders to ensure its dual functionality as a flood reservoir and a public amenity. These examples underscore the importance of fostering trust through transparent communication and participatory design processes.

Cross-sector collaboration is equally pivotal. Publicprivate partnerships (PPP) unlock both funding and technical expertise, ensuring that projects balance the interests of diverse parties. Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands is a case in point, integrating public utilities with private retail and leisure spaces in a way that maximises both economic and social returns. Such examples highlight the potential of collaborative frameworks to deliver projects that are not only functional but also economically viable and socially inclusive.

STRATEGIES FOR NAVIGATING STAKEHOLDER DYNAMICS

Successfully managing stakeholder dynamics in underground urban development demands a thoughtful, multi-faceted approach.

Early and sustained engagement with stakeholders is a cornerstone of effective project delivery. Initiating conversations during the feasibility stage fosters alignment of objectives, mitigates potential conflicts, and builds trust. Innovative tools such as 3D modelling and participatory design workshops play a pivotal role in this process, offering stakeholders clear visualisations of project plans and their impacts. A prime example is London’s Crossrail project, which engaged a range of stakeholder groups from the outset. This proactive approach not only minimised disruptions but also ensured the preservation of cultural landmarks, demonstrating the value of inclusive planning.

Collaboration across sectors amplifies the potential for success, bringing together the financial resources and technical expertise of public and private entities. Such partnerships are instrumental in balancing diverse and often competing interests. Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands development is a case in point, where the integration of public utilities, private retail, and transit systems created a seamless underground network that maximises utility and accessibility. The project’s success illustrates how collaboration can result in infrastructure that serves both public and commercial needs without compromising on design or functionality.

Transparent communication is another critical element in navigating stakeholder dynamics. Clear and consistent messaging builds public trust, alleviates concerns, and reduces resistance to large-scale projects. The revitalisation of New York’s subway system exemplifies this principle. Through community forums and regular updates, project leaders ensured public buyin even amidst temporary inconveniences such as station closures and service disruptions. This transparency not only kept the public informed but also maintained confidence in the project’s broader goals.

By integrating early engagement, cross-sector collaboration, and transparent communication, subterranean developments can navigate the complexities of stakeholder dynamics, ensuring projects are not only technically sound but also socially supported and economically viable.

DESIGNING FOR MULTI-USE FUNCTIONALITY

In dense urban areas, subterranean spaces must serve multiple purposes to maximise value and efficiency. This requires meticulous planning and advanced technical solutions. Key principles for multi-use design of underground space:

- Layered zoning: Allocate specific depths to particular uses—utilities at deeper levels, transport systems mid-level, and pedestrian or retail spaces closer to the surface. Example: The Kansai International Airport in Osaka incorporates underground baggage handling systems and flood mitigation infrastructure, freeing the surface for passenger terminals.

- Modular and adaptive spaces: Design spaces with future adaptability in mind, allowing reconfiguration as urban needs evolve. Helsinki’s underground subway stations are designed to double as emergency shelters, showcasing flexibility in function.

- Integrated smart systems: Use Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Digital Twins to optimise layouts, prevent clashes between systems, and monitor long-term performance. Example: Hong Kong’s MTR Corporation uses AI to synchronise train schedules, lighting, and air conditioning across its underground network, ensuring energy efficiency and user comfort.

RESOLVING COMPETITION FOR SPACE

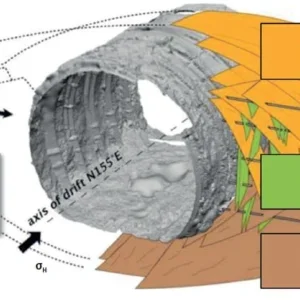

Subterranean space is finite and often crowded with legacy infrastructure like utility lines, foundations, and geological features. Effective management of this competition is critical to the success of underground projects.

Comprehensive subsurface mapping

This is a critical first step in resolving these conflicts. Ground penetrating radar, LiDAR, and GIS technologies can create detailed inventories of underground assets, enabling informed decision-making. Rotterdam’s underground planning efforts, for example, rely on a subsurface atlas that documents utilities, aquifers, and soil conditions, helping planners navigate complex spatial constraints.

Dynamic policy frameworks

Adaptive zoning laws can prioritise high-impact uses of underground space while streamlining approval processes. Singapore’s Underground Master Plan balances public and private interests by designating specific zones for utilities, transport, and commercial activities. Meanwhile, financial incentives, such as tax breaks or grants, encourage innovation and investment in sustainable subterranean developments.

In London, the Crossrail project benefitted from such incentives, attracting private investment to tackle the engineering complexities of tunnelling beneath one of the world’s busiest cities. By aligning technical innovation with economic strategy, projects can overcome the inherent challenges of subterranean development.

SUSTAINABILITY AT THE CORE

Underground developments, while solving spatial and functional challenges, must also align with and advance overarching sustainability objectives. The convergence of engineering innovation, material science, and urban planning creates opportunities for subterranean spaces to actively contribute to environmental resilience, energy efficiency, and climate adaptation.

Energy-efficient systems are central to the sustainable operation of underground spaces. Geothermal cooling and heating systems, for example, leverage the Earth’s stable subsurface temperatures to reduce the reliance on fossil fuels for temperature regulation. By combining this with LED lighting, which consumes significantly less energy than traditional lighting, and heat recovery systems that recycle excess heat from mechanical processes, underground facilities can drastically cut operational emissions.

Stockholm’s underground data centres provide a compelling case study: the waste heat generated from their operations is channelled to warm thousands of homes, creating an energy-efficient circular system. This innovative approach not only reduces the carbon footprint of the data centres but also offsets heating demands for urban residents, blending technological and environmental benefits seamlessly.

The materials chosen for underground construction also play a critical role in sustainability.

Traditional construction materials, such as concrete, have significant embodied carbon footprints, making the adoption of low-carbon alternatives imperative. The Brenner Base Tunnel project, between Austria and Italy, serves as a benchmark that showcases the use of lowcarbon concrete, which incorporates supplementary cementitious materials to reduce emissions. Additionally, recycled aggregates and steel can replace virgin materials without compromising structural integrity, further contributing to a reduced environmental impact.

Flood resilience and seismic stability must also be prioritised in the design of underground spaces, particularly as cities face intensifying climate risks. Tokyo’s ‘G-Cans Project’ illustrates the dual functionality of subterranean infrastructure in mitigating climate impacts while enhancing urban usability. As one of the world’s largest underground flood management systems, ‘G-Cans’ captures and stores stormwater during heavy rainfall, reducing the risk of surface flooding. Beyond its engineering brilliance, this facility doubles as a public space, hosting tours and educational programmes, effectively integrating utility and community engagement.

Advanced technological solutions are also emerging to make underground spaces more adaptive to changing environmental conditions. Sensors embedded in underground structures can provide real-time data on stress, temperature, and water infiltration, enabling predictive maintenance and reducing the risk of failure. IoT-based systems can optimise energy consumption, lighting, and ventilation by dynamically responding to occupancy and environmental factors.

Finally, integrating underground planning with broader urban sustainability frameworks is essential. Subterranean developments should complement surface-level green spaces, enabling cities to meet biodiversity goals while maintaining dense urban cores.

For instance, Helsinki’s Underground Master Plan prioritises underground facilities for utilities and parking, leaving surface areas open for parks and pedestrian zones, thereby enhancing urban liveability and ecological health.

In summary, sustainability in underground planning is not merely an add-on but an imperative that transforms challenges into opportunities. By adopting energyefficient systems, utilising low-carbon materials, incorporating climate-resilient designs, and leveraging advanced technology, subterranean developments can serve as models for sustainable urban infrastructure, addressing the dual imperatives of environmental stewardship and urban functionality.

THE PATH FORWARD:

BUILDING THE CITIES OF TOMORROW

The underground is not merely a space—it is an opportunity to redefine how cities grow, connect, and thrive. Projects like New York’s subway, Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands, and Helsinki’s Underground Master Plan reveal the transformative potential of subterranean development when guided by strategic stakeholder engagement, innovative design, and a commitment to sustainability.

For architects, engineers, designers, geographers, geologists and planners, the challenge is clear: to design and execute underground projects that are not only technically sound but also sustainable, adaptable, and inclusive. The question is no longer why we should build underground, but how boldly and effectively we can do so to shape the cities of tomorrow.