Across the world cities are getting overcrowded and the ratio of the world’s urban population is expected to increase from 55% in 2018 to 68% by 2050, according to the United Nations.

Metro systems need to be improved to offer easier and faster urban connections. This process might affect congested foundations of the buildings above, which require a detailed research to progress through underground spaces.

In October 2019 the British Tunnelling Society had a meeting at the University of Northumbria on “Tunnelling under 21st century building structures is not easy: Bond Street Station Upgrade (BSSU) and the infamous case of Avon House”. The presentation described the scheme, the building damage assessment and the mitigation taken from three members of the project team, Paul Perry, associate director of Hewson consulting engineers (formally Halcrow Atkins), Richard Totty, Bachy Soletanche, Andy Clarke, Costain.

The BSSU project was to upgrade the station to reduce congestion to a crowded station and to provide step free access.

This was achieved by providing a new station entrance and satellite ticket hall on the north side of Oxford Street, a new route to the Jubilee Line with improved interchange between the lines, new lifts and escalators, connections to existing London Underground infrastructure and a direct connection to the new Crossrail Bond Street station.

The project has been completed in Christmas 2017. The client was London Underground while Costain and Laing O’Rourke were design and build contractors in joint venture with the Halcrow Atkins joint venture (HAT) for completion of the detailed design.

Following the BTS meeting in an interview with T&T, Perry explains that in terms of design process they looked at the existing buildings after the building damage assessment. This procedure aims to cover all range of buildings. Perry says, “When we looked at the new railway line and the Bond Station capacity upgrade incorporated in the Crossrail scheme, there were many high level buildings, which ended up needing more investigations to understand how they were put together, designed and built.

Avon House is 1930’s steel framed building and it was altered over a number of years by the insertion of transfer beams in the upper floors to allow a more open space for the Oxford Street retail area.

Perry adds that the peculiar aspect for Avon House was related to the original construction with a regular column grid and the intended use was a standard building. This building was taken over by HMC Music store in late 1990’s. This steel framed building was opened it up by strengthening and searching the transferring structure on the first floor.

Thus, it was possible to further reduce the number of columns in the building.

Perry explains that Avon House was a “good example” to show the need to identify this type of building quite in advance to have the time to research, open up and investigate.

“Avon House went through a self-risk assessment and ended up needing much more work on it,” says Perry. “The unique source was a listing building and it was mixed use with offices above and retailers below and there were hotspots on the footprint of the building with a large load that put at risk foundations.

“If you are tunnelling underneath hotspots you need to consider that you are going to set up movements, which might affect the building far greater than normal and it is just a standard for the Victorian buildings.”

“The process of tunnelling underneath a transfer structure is also unique because we don’t need to tunnel once but twice as we had to dig a tunnel coming into below the building.” By connecting two vertical shafts, a passage lift has been formed to enable an improved disabled access from the ground to the deep platform tunnel.

This became quite troublesome because the heaviest load columns were above the largest area to be excavated in the tunnelling – except two new tunnels connected to the vertical shafts”. In terms of settlement, the initial guidance was between 5 and 10mm.

Once the actual site conditions were detected and a safe guidance on the ground slope was established, the differential settlement between columns was set at 25mm. Perry explains that the plan is to make sure that they would never get to this level (25mm) and if they get it, they have to mitigate it.

“The uniqueness of this is an arrangement between London Underground, Transport for London and the Building Owner to discuss what needs to be done for the tunnelling contract and what needs to be done to protect the building,” says Perry. During tunnelling works it has been decided to refurbish the building due to a change in tenant from HMC retail store to Forever 21.

Perry adds, “We had to share information on the building weekly to tunnel underneath and in fact I was fortunate enough to have known in previous works the design transfer structure.

“We had to make sure that we were working within the limit (25mm differential) and how it would have affected the building.

“We had to extract the existing information going through archives and libraries contacts to get to our analysis and then give us more details on the building.

“Specifically we needed the drawing of ‘As-built conditions’ when it was refurbished in 1987.”

Some structure investigations were required, so they ended up going into the building with the blessing of the owner and taking off the plaster, breaking the concrete steel works in a number of levels through the height of the building to determine the connections between the beams and the columns. That was relevant to get better information and to fit them into the analysis.

As Perry explains, they found that the building was able to tolerate more movement and more differential settlement than what was expected. The main mitigation as ground improvement was compensation grouting.

The grouting phases included pre-conditioning, active compensation during tunnelling and corrective after tunnelling.

The main geological formations were Made Ground, River Terrace Deposits (RTD) and London Clay. The drilling geometry was with sleeved pipes to allow discrete injections to grout. The ground movements were monitored with in-place inclinometers and the water pressure with piezometers.

Perry says that they were able to set up an efficient rate of drilling and grouting underneath the building avoiding the existing sewers and foundations with the information that they got and then they came up with an improved model.

In terms of structural damage, a debate was raised about movements of the building related to finishes such as suspended ceilings, which are attached to the structure. Perry clarifies that there are fairly flexible ceilings and joints and of course they move. Perry says that there was also a discussion of what is acceptable and this is a matter of the damage criteria.

“At the moment our rulebook on damage classification is not translated in modern architecture that we are dealing with it,” says Perry. “We didn’t find a particular damage on the building and we were able to control what we were grouting. As the building was stiffer, we were able to see that the differential settlement was not increased.”

Regarding the volume loss at Avon House, Crossrail went through this data and it was up to 0.7%. “When we were undertaking the analysis we were near 1.5%,” says Perry. “I think 0.7% reflects how the tunnelling industry is going in these days.

In terms of dealing with certain figures and risks, this industry is much more mature to take practical measures and to prevent the effects of these movements. There is a range of settlement associated with volume loss and you need to deal with it. There is also a range for existing buildings because you have a flexible connection on the buildings and they are fixed stiffer and we have to deal with them.”

The Importance of Avon House

Perry explains that Avon House is a practical case history that highlights the need for changing the process to discuss and get information in advance.

“The feeling in the industry is that the damage assessment when you look at railway line is becoming more like a factory process and the trouble is that it is a repetitive process and you can miss some details,” says Perry. “This happens across the world as buildings are now becoming more sensitive and for this reason Avon House became a case history.

“However, it is not just the procedure to look at the damage effect of a building. In 1970’s and 1980’s many buildings in London were demolished but if you are looking at refurbishing existing buildings, a lot of them were old Victorian houses with load parts or soils to extend to London Underground.

“Nowadays we need to do more in terms of structures or iconic architecture design with sensitive glass and atrium. In this way we might be able to expand our metro system in the future.”

Recommendations

When a sufficient detailed guidance is not available, Perry advises a good interaction between the client, property owners, insurers, lawyers, design team engineers to assess the damage criteria.

Perry explains that there are no codes on design to establish the slope underneath and get a specific limit.

“One of the recommendations from Avon House is that we do need to look at that more, we do need to change the old way to work,” says Perry. “We got the same briefings of tunnelling underneath existing buildings, but we have got to the end. We have to consider the slope, what material to take, what safety structures, what needs to be polished.”

Perry highlights the need to get more guidance on glass façades on determining the use of buildings and therefore identifying unusual structures such as the transfer structure in Avon House. “In Crossrail 2 the use of drones is being considered because they need to look at thousands of buildings at a certain level to be confident in programme and cost,” says Perry.

“Sending a drone up and looking at a building is not ideal because you can only get some indications but you can’t go into it to see the skeleton.

“For difficult buildings like Avon House we need more time to investigate before tunnelling because we can’t tunnelling and investigating at the same time. Of course not all the buildings, especially new ones, need a detailed option.”

Perry explains that what they need is a better judgement because there is a better checklist than sending a drone and taking pictures. “It would be more appropriate a walk-in survey with a structural engineer,” says Perry.

“We need to combine the damage list and to identify the appropriate measure to prevent any damages.”

In terms of expected analysis, Perry adds that a transfer structure should be considered like a hotel. “We have to find spaces for bedrooms and open areas for receptions and car parking below,” says Perry. “Thus you have two transfers, one for bedrooms and reception above and then you have got the large area below for a car park. You can walk through that and understand how the transfers can be set up in an appropriate way to assess the building.”

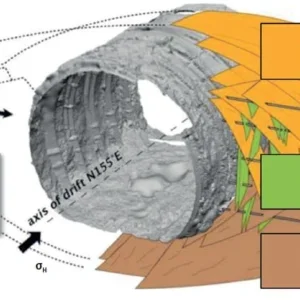

Perry adds that it is helpful to check records and drawings in 3D to see the movements of the building in three dimensions and to get realistic mitigation measures.